It was not unusual for my father, Detective Inspector Eric Morley, to show me scenes of crime photographs and ask me to use my “grasshopper mind,” as he called it, to say anything I thought about the pictures. He returned all the files and photographs except one, which was of himself, showing his broken nose after he was involved with a fracas with the serial killer Michael Copeland (Eric always said "You should have seen Copeland!”).

Of course, nowadays this would be seen as inappropriate as I was probably aged about 14 at the time. Most of his family either worked for the LMS railway or in the coal mines, but Eric was academic enough to attend grammar school (Tapton House) but left at 15 to join Chesterfield police where his first assignment was on the Ambulances. He retired after 30 years’ service with Derbyshire constabulary after spending most of the time with C.I.D and a short period with Special Branch. Naturally he wanted me to follow in his footsteps and join the police, but even from an early age I realised the huge amount of stress and strain the job had put on my father, unfortunately not always due to the felons.

I left Westfield comprehensive school at 16. I had struggled academically in the bottom half of the grammar school stream but I excelled in sport, especially rugby. I could have stayed on to sit my A levels, but my parents moved from Eckington and bought their first house together in Hasland. So, I enrolled at Chesterfield College on a Pre P.E. teachers’ course. It was whilst I was there that a lecturer from the English Literature department at Sheffield University, Barry Hines, gave a talk on writing. I was the only student to stay back for questions and spent an hour or so with the author of “A Kestrel for a Knave.” His sporting background and working-class background were not dissimilar to my own.

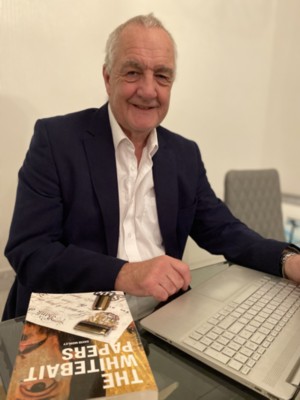

After he retired from the police, my father worked as an investigations officer for the Jockey Club. Occasionally he would take me along to help out. During the long drives he would reminisce about the cases and incidents of his former life. On one occasion he told me the story about his father’s younger brother, his Uncle Bob, and how he found out about his Special Branch record. I was intrigued and decided to write up the story as “The Doubleday Connection.” I used many of my father’s anecdotes (and a few of my own) in the narrative of Doubleday and later, in my other works.

I worked for North-East Derbyshire recreation department, then when Rugby Union became a professional game, I became a coach. I also worked at Chesterfield College with the ‘Pre 16’ group which was my first experience with working with Special Educational Needs (SEN) students. Throughout this time, I continued to write.

The stories I write have one major problem. I can’t spell and my punctuation is terrible. Once, at school I had to stay behind and write out the word “would” a hundred times. I told the teacher that “would” should be written as “wud” and, after I had been scolded for getting it wrong, wrote “wood” instead of “would” as I thought it was right and logical.

Before the invention of spellcheck my wife Anne would read through my stories. As an academic and a member of Mensa she would be as frustrated as me with my efforts. I sold a few story ideas to publishers and script writers and eventually had an offer from a London firm to publish “The Doubleday Connection,” but they later wanted to give it to one of their inhouse authors. As the story came from my father, I refused and so the project was shelved.

Grasshopper Mind, ADHD and me

It was whilst working at Chesterfield college with the SEN group that I first heard the term ADHD. I believed at the time that it was just an excuse for bad behaviour, but after attending courses began to realise that I was on the spectrum, as I now know are many others. Being able to identify the causes for a “grasshopper mind” and realising not all people think the same way as you do has enabled me to understand my own frustrations, that have led to depression and why others are frustrated by me and often fail to understand where I am coming from.

I don’t believe the term SEN should be used, as now the term “Special” is deemed as derogatory. Everyone is different and peoples’ needs are different not special. Time should be taken to find out how best to apply this principle. I have worked towards this with my business “Tryline” that I set up 25 years ago and have had much success working with students.

Last year, at the age of 63, I attended a meeting with a senior manager of a large company and its Head of Human Resources. I was asked what triggers an attack of ADHD. My mind went blank over such an uninformed question. I later replied to it by email……

"You asked me at the meeting what triggers my ADHD and I was unable to answer you clearly. Having had time to process the question I would like to answer it now. There is no trigger to ADHD: it is a condition like dyslexia and autism and like these has been misunderstood until relatively recently, particularly where it occurs in adults. It is a process of thought. I wake up with it. There is no filter to your thoughts and you can have several ideas jumping in and out of your mind in a short period of time. Some of these ideas are unique and brilliant, others not so …"

I hope that some of the “other” thoughts have been filtered out in my books.